Name: Mickey Charles Mantle

Date of

Birth: October 20, 1931

Place of

Birth: Spavinaw, Oklahoma

Grew Up

In: Commerce, Oklahoma (about 46 miles to the northeast of Spavinaw, 93 miles northeast of Tulsa; the closest big-league city now is Kansas City, 164 miles to the north; then, it was St. Louis, 310 miles to the northeast)

Nationality: English

Position: Center field

Batted: Switch-hitter

Threw: Righthanded

Nickname(s): The Mick, Muscles, the Commerce Comet, Slick (a nickname he and Whitey Ford called each other)

Family: Father Elvin, known as Mutt, worked in the lead and zinc mines of northeastern Oklahoma, as did most of his relatives; it was inhaling the dust from those mines that killed the Mantle men by their early 40s, not any "curse" Mickey could think of. His mother, the former Lovell Richardson, was a housewife. He had 2 brothers, also scholastic athletes.

He married Merlyn Johnson, and had four children: Mickey Jr., Billy, Danny and David. Billy was named for Yankee teammate and close friend Billy Martin, whose real name was Alfred. But then, Mutt had named his son after a Baseball Hall-of-Famer, Mickey Cochrane. (Just as Willie Mays was born Willie, not William, Mantle's real first name was Mickey, not Michael.) Cochrane's real first name was Gordon, and Mickey always said he was glad he wasn't named Gordon Mantle. (Which sounds like the name of a lawyer to me.)

Mutt died of Hodgkin's disease in 1952, at the beginning of Mickey's 2nd season. Billy also died of Hodgkin's, in 1994, shortly after Mickey got out of rehab; while so many people were afraid it would restart his drinking, just as his father's death was its original accelerant, he stayed sober. Lovell died in 1995, a few weeks before Mickey's transplant. Mickey Jr. died in 2000. Merlyn died in 2010. At this writing, Danny and David are still alive, and the official caretakers of Mickey's image. They were consultants on the film 61*, which included a scene of David and his then 4-year-old son Will, watching Thomas Jane as Mickey hit one out. David stood in for Mickey at the last game at the old Yankee Stadium, wearing his Number 7 uniform and walking out to center field.

Before He Was a Yankee: Starred in football and basketball at Commerce High School, but the school didn't have a baseball team, so he played on amateur squads in that region where Oklahoma, Kansas, Missouri and Arkansas all come together. (The nearest real city was Joplin, Missouri.)

He married Merlyn Johnson, and had four children: Mickey Jr., Billy, Danny and David. Billy was named for Yankee teammate and close friend Billy Martin, whose real name was Alfred. But then, Mutt had named his son after a Baseball Hall-of-Famer, Mickey Cochrane. (Just as Willie Mays was born Willie, not William, Mantle's real first name was Mickey, not Michael.) Cochrane's real first name was Gordon, and Mickey always said he was glad he wasn't named Gordon Mantle. (Which sounds like the name of a lawyer to me.)

Mutt died of Hodgkin's disease in 1952, at the beginning of Mickey's 2nd season. Billy also died of Hodgkin's, in 1994, shortly after Mickey got out of rehab; while so many people were afraid it would restart his drinking, just as his father's death was its original accelerant, he stayed sober. Lovell died in 1995, a few weeks before Mickey's transplant. Mickey Jr. died in 2000. Merlyn died in 2010. At this writing, Danny and David are still alive, and the official caretakers of Mickey's image. They were consultants on the film 61*, which included a scene of David and his then 4-year-old son Will, watching Thomas Jane as Mickey hit one out. David stood in for Mickey at the last game at the old Yankee Stadium, wearing his Number 7 uniform and walking out to center field.

Before He Was a Yankee: Starred in football and basketball at Commerce High School, but the school didn't have a baseball team, so he played on amateur squads in that region where Oklahoma, Kansas, Missouri and Arkansas all come together. (The nearest real city was Joplin, Missouri.)

Acquired By Yankees: Yankee scout Tom Greenwade stalked Mickey until graduation in 1949, and then offered Mickey a $1,500 signing bonus -- about $15,000 in today's money.

(Around the same time, the Pittsburgh Pirates offered St. John's University star Mario Cuomo a $2,000 bonus. Cuomo got beaned and went into law and politics, while Mickey's many injuries never included a serious beaning. He liked to joke about how the Yankees got more value for him than the Pirates got for the future Governor and father of another future Governor.)

Mickey spent the rest of the 1949 season and all of 1950 in the minor leagues, before his prodigious home runs in spring training led to his going north with the team. He made his Yankee debut on April 17, 1951, at Yankee Stadium, against the Boston Red Sox. His first at-bat was a groundout off Bill Wight, but he went 1-for-4 with an RBI single, and Jackie Jensen hit a home run, backing the shutout pitching of Vic Raschi, as the Yankees won 5-1.

Uniform Number(s) as a Yankee: Was originally given 6. The progression seemed natural: Babe Ruth wore 3, Lou Gehrig wore 4, Joe DiMaggio wears 5, and Mickey is supposed to replace Joe, so he gets 6. It seemed to fit, as Mickey's baseball hero was Stan Musial of the St. Louis Cardinals, and Stan the Man wore 6.

But Mickey struggled at first, and was sent down to the minors. His slump continuing with the Triple-A Kansas City Blues, he called his father in Oklahoma, telling him he wanted to quit baseball. Mutt wasn't having it: He drove up, and reamed Mickey out: "You can come work in the mines like me. I thought I raised a man. You ain't nothin' but a coward." The tough love shocked Mickey into begging his father for another chance, and he took it, hitting so well that he got called back up to the Yankees.

By this point, Cliff Mapes -- by a twist of fate, also the last Yankee to wear 3 before it was retired for Ruth -- had been traded, making 7 available. Mickey was given 7, and the rest is history. Until 42 was universally retired for Jackie Robinson, no other baseball player was more identified with a single uniform number than Mickey was with 7.

Yankee Achievements Include: 536 home runs, including 266 at Yankee Stadium, making him the ballpark's all-time leader. He was only the 6th member of the 500 Home Run Club, and was 3rd on the all-time home run list when he retired, trailing only Ruth and Mays. (Hank Aaron soon surpassed him.) While several players have surpassed him -- most recently, Albert Pujols -- he remains the all-time leader among switch-hitters.

His home runs were every bit as long as Ruth's: Mickey hit, or may have hit, the longest home runs ever at the original Yankee Stadium, Comiskey Park in Chicago, Tiger Stadium in Detroit, Cleveland Municipal Stadium, Sportsman's Park in St. Louis, Shibe Park (a.k.a. Connie Mack Stadium) in Philadelphia, and, most notably, Griffith Stadium in Washington, a drive that was unofficially measured at 565 feet. (Every account of that 1953 drive says that the ball glanced off an auxiliary scoreboard before continuing into a backyard. The distance shouldn't be measured from home plate to where the ball stops, but from the plate to where it first hits something. That was still a 460-foot shot.) Yankee publicity director Red Patterson's desire to measure Mickey's drives gave rise to the term "tape measure home run."

Four times, he hit the frieze (a.k.a. "the facade") on the roof at old Yankee Stadium. Twice lefthanded, to right field, within a month, in May 1956; once righthanded, to left field, in 1957; and again lefthanded, to right field, a walkoff home run against the Kansas City Athletics on May 22, 1963, supposedly six inches from the top. This was the closest any player ever came to hitting a fair ball out of The Stadium.

(Frank Howard is also sometimes credited with hitting the facade in left field, although this is unproven. The story that Negro Leaguer Josh Gibson hit a fair ball completely out of the old Yankee Stadium has been researched. Accounts from black-owned, -operated and -targeted newspapers, such as New York's Amsterdam News, the sources most likely to say that it happened, if it did, show that Gibson played in Yankee Stadium many times, and hit some long home runs, but they never reported that he hit one all the way out. That's not conclusive, but it is telling that the sources most likely to say that it happened at the time didn't say so.)

Mickey led the American League in home runs four times. Only once did he lead it in batting average or runs batted in, but in that year, 1956, he led in all three, winning the Triple Crown. Indeed, he led both Leagues in all three of those categories, and he is still the last man to do that. He was named AL Most Valuable Player in 1956, 1957 and 1962.

He was named to the All-Star Team 20 times -- despite playing in only 18 seasons. From 1958 to 1962, there were two All-Star Games each season. Mickey reached the All-Star Game every season from 1952 to 1965, and again in 1967 and '68, so he made it in 16 of his 18 seasons. The Gold Glove Award only started in 1957, and he won it only once, in 1962. Nevertheless, he was regarded as a very good center fielder, including making a catch of a Gil Hodges drive that saved Don Larsen's perfect game in Game 5 of the 1956 World Series -- a game in which Mickey also homered.

He hit 18 home runs in World Series play. While other players have hit as many, or more, in postseason play, it remains a record just for the Series. His 16th, which broke Ruth's record, was what we would now call a walkoff home run, in Game 3 of the 1964 World Series against the Cardinals, his boyhood team.

Because of the rapid growth of television in the 1950s, and the Yankees' frequent appearances on national broadcasts, including the 12 World Series -- 7 of them won by the Yankees -- during Mickey's career, he became baseball's first television superstar, and thus the most popular player among the Baby Boom generation, even if, by his own admission, he wasn't as good as Mays or Aaron.

He played in 2,401 games as a Yankee, a club record until surpassed by Derek Jeter in 2011. He frequently said, "I played in more games as a Yankee than anybody. Nobody knows that." He did all of these things despite countless injuries, particularly to his knees, and despite his constant off-field carousing, including prodigious drinking and womanizing. (The womanizing was mostly kept quiet during his lifetime, but stories of his drunken behavior simply couldn't be stopped.)

Highest Salary: $100,000, first received in 1963. About $780,000 in today's money. In a 1991 interview, he said, "They couldn't pay me, Joe DiMaggio, Willie Mays, Hank Aaron, Ted Williams, Stan Musial today."

Something

you should know about him, if you don’t already: Mickey had a nephew, Kelly Mantle, who has become a renowned drag queen and recording artist.

Left

Yankees: After being switched to left field in 1965, and then first base in 1967, as spring training dawned on March 1, 1969, he decided, "The young kids are just gettin' too fast for me," and confirmed what everyone had believed all through 1968: He was retiring.

His last game was on September 28, 1968, at Fenway Park. He popped up to short against Jim Lonborg in his first at-bat, and was then replaced in the field by Andy Kosco. The Yankees bailed Mel Stottlemyre out of a 3-0 jam, and beat the Boston Red Sox 4-3, Lindy McDaniel the winning pitcher over Lonborg.

His last game was on September 28, 1968, at Fenway Park. He popped up to short against Jim Lonborg in his first at-bat, and was then replaced in the field by Andy Kosco. The Yankees bailed Mel Stottlemyre out of a 3-0 jam, and beat the Boston Red Sox 4-3, Lindy McDaniel the winning pitcher over Lonborg.

After He

Was a Yankee: Became a Yankee coach and a broadcaster, but held neither post for long. Lost a lot of money with bad investments, including in Mickey Mantle's Country Cookin' Restaurants and a temporary-placement agency he and Joe Namath put their names on, Mantle Men and Namath Girls. (Nice name. It was 1969.) But he missed playing terribly. Depression kicked in, and his drinking accelerated again.

The 1950s nostalgia wave that began in the early 1970s, and the baseball memorabilia craze, kicked in, and he ended up making more money every year being a retired baseball legend than he did when he was an active player. He made commercials for everything from Brylcreem (which was the first time I ever saw him on TV) to beer. With Mays, he did commercials for butter and for USA Today. While he maintained friendships with Mays, Aaron, Williams and Musial, stayed friends with Ford and Martin, and became friends with later Yankee star Reggie Jackson, his relationship with his predecessor in Yankee Stadium's center field, DiMaggio, remained frosty -- for reasons known only to Joe.

Mickey Mantle's Restaurant opened on Central Park South in 1988. It was loaded with baseball memorabilia, and the chairs were designed to look like seats at the old Stadium, with every one having the number 7 on them. Mickey visited every time he came to New York, although radio bully Don Imus liked to joke that, "Your meal is free if you can guess which table Mickey is under." Mickey insisted that the prices be kept low, because he wanted the place to be affordable for families. I ate there once, and, to be honest, the food was not up to the level of the decor. Due to rising rent, the restaurant closed in 2012. A new Mickey Mantle's Steakhouse is open across from the new Oklahoma City ballpark, Chickasaw Bricktown Ballpark. Appropriately, the Steakhouse's address is 7 South Mickey Mantle Drive.

In 1988, Mickey left Merlyn and their house in a suburban section of Dallas, and bought a house in the suburbs of Atlanta, near the home of Greer Johnson, his new girlfriend and agent. But he never divorced Merlyn.

Died: August 13, 1995, at Baylor University Medical Center in Dallas, from cancer, the result of his 45 years of hard drinking. Late in 1993, he'd been told by a doctor that his next drink could be his last, and he checked into the Betty Ford Center. He seemed to be in recovery. But his liver was weakened and stricken with cancer. He received a liver transplant on June 8, 1995 -- 26 years to the day after his Day at The Stadium -- and began to speak out on behalf of sobriety and organ donation. But the cancer had already spread to his lungs, and he never had a chance. He was 63.

On the day of his death, the Yankees were scheduled to play the Cleveland Indians at home. The Yankees had black armbands sewn onto their left sleeves, and, before leaving for a roadtrip that night, would have black 7s sewn above them. Dave Winfield was playing for the Indians, and Andy Pettitte and Mariano Rivera were rookies on the Yankee roster. (Derek Jeter and Jorge Posada had both played for the Yankees by this point, but were not on the roster at the time.) The first batter of the game was the Indians' Kenny Lofton -- a center fielder wearing Number 7. He flew out to Bernie Williams -- in center field.

At his press conference after his transplant, Mickey had said, "You talk about a role model, this is a role model: Don't be like me." At his funeral in Dallas, broadcaster Bob Costas said, "In the last year of his life, Mickey Mantle, always so hard on himself, finally came to accept and appreciate the distinction between a role model and a hero. The first, he often was not. The second, he always will be. And, in the end, people got it."

But his death was still a blow. When Elvis Presley died in 1977, it was an inescapable sign that the Baby Boomers, now in their 20s, weren't kids anymore. When Mickey Mantle died in 1995, it was a new marker, for these people now in their 40s: Now, they were getting old.

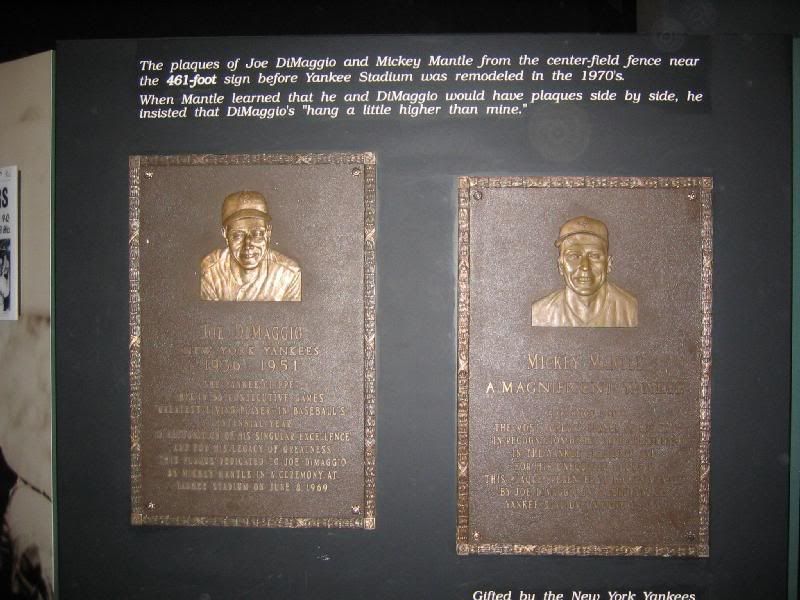

Plaque Dedicated: June 8, 1969, Mickey Mantle Day. His retired Number 7 was presented to him by Ford, and his Plaque was presented to him by DiMaggio -- who had to be wondering, "Hey, what about me? If Mickey's getting one, then, obviously, they don't just do it for dead players. So why didn't I get one when I retired?" Before beginning his speech, Mickey told the crowd he had the honor of presenting Joe with his Plaque, and said, "It oughta hang just a little higher than mine." Joe seemed genuinely moved by the gesture, although he seemed to have some kind of problem with Mickey that never went away.

The Plaques were hung on the outfield wall the next Opening Day, April 12, 1970 -- and, sure enough, Joe's was one inch higher than Mickey's. With the other Plaques and the Monuments, they were moved to Monument Park in 1976.

After Mickey's death, his Plaque was removed, and replaced by a Monument that was dedicated on August 25, 1996. When Joe died in 1999, his Plaque was also replaced with a Monument. The original Plaques are now on display at the Yogi Berra Museum & Learning Center in Little Falls, New Jersey. Unfortunately, this is the best picture I can find of them, and the text isn't very legible, due to the glare of a flash bulb.

The 1950s nostalgia wave that began in the early 1970s, and the baseball memorabilia craze, kicked in, and he ended up making more money every year being a retired baseball legend than he did when he was an active player. He made commercials for everything from Brylcreem (which was the first time I ever saw him on TV) to beer. With Mays, he did commercials for butter and for USA Today. While he maintained friendships with Mays, Aaron, Williams and Musial, stayed friends with Ford and Martin, and became friends with later Yankee star Reggie Jackson, his relationship with his predecessor in Yankee Stadium's center field, DiMaggio, remained frosty -- for reasons known only to Joe.

Mickey Mantle's Restaurant opened on Central Park South in 1988. It was loaded with baseball memorabilia, and the chairs were designed to look like seats at the old Stadium, with every one having the number 7 on them. Mickey visited every time he came to New York, although radio bully Don Imus liked to joke that, "Your meal is free if you can guess which table Mickey is under." Mickey insisted that the prices be kept low, because he wanted the place to be affordable for families. I ate there once, and, to be honest, the food was not up to the level of the decor. Due to rising rent, the restaurant closed in 2012. A new Mickey Mantle's Steakhouse is open across from the new Oklahoma City ballpark, Chickasaw Bricktown Ballpark. Appropriately, the Steakhouse's address is 7 South Mickey Mantle Drive.

In 1988, Mickey left Merlyn and their house in a suburban section of Dallas, and bought a house in the suburbs of Atlanta, near the home of Greer Johnson, his new girlfriend and agent. But he never divorced Merlyn.

Died: August 13, 1995, at Baylor University Medical Center in Dallas, from cancer, the result of his 45 years of hard drinking. Late in 1993, he'd been told by a doctor that his next drink could be his last, and he checked into the Betty Ford Center. He seemed to be in recovery. But his liver was weakened and stricken with cancer. He received a liver transplant on June 8, 1995 -- 26 years to the day after his Day at The Stadium -- and began to speak out on behalf of sobriety and organ donation. But the cancer had already spread to his lungs, and he never had a chance. He was 63.

On the day of his death, the Yankees were scheduled to play the Cleveland Indians at home. The Yankees had black armbands sewn onto their left sleeves, and, before leaving for a roadtrip that night, would have black 7s sewn above them. Dave Winfield was playing for the Indians, and Andy Pettitte and Mariano Rivera were rookies on the Yankee roster. (Derek Jeter and Jorge Posada had both played for the Yankees by this point, but were not on the roster at the time.) The first batter of the game was the Indians' Kenny Lofton -- a center fielder wearing Number 7. He flew out to Bernie Williams -- in center field.

At his press conference after his transplant, Mickey had said, "You talk about a role model, this is a role model: Don't be like me." At his funeral in Dallas, broadcaster Bob Costas said, "In the last year of his life, Mickey Mantle, always so hard on himself, finally came to accept and appreciate the distinction between a role model and a hero. The first, he often was not. The second, he always will be. And, in the end, people got it."

But his death was still a blow. When Elvis Presley died in 1977, it was an inescapable sign that the Baby Boomers, now in their 20s, weren't kids anymore. When Mickey Mantle died in 1995, it was a new marker, for these people now in their 40s: Now, they were getting old.

Plaque Dedicated: June 8, 1969, Mickey Mantle Day. His retired Number 7 was presented to him by Ford, and his Plaque was presented to him by DiMaggio -- who had to be wondering, "Hey, what about me? If Mickey's getting one, then, obviously, they don't just do it for dead players. So why didn't I get one when I retired?" Before beginning his speech, Mickey told the crowd he had the honor of presenting Joe with his Plaque, and said, "It oughta hang just a little higher than mine." Joe seemed genuinely moved by the gesture, although he seemed to have some kind of problem with Mickey that never went away.

The Plaques were hung on the outfield wall the next Opening Day, April 12, 1970 -- and, sure enough, Joe's was one inch higher than Mickey's. With the other Plaques and the Monuments, they were moved to Monument Park in 1976.

After Mickey's death, his Plaque was removed, and replaced by a Monument that was dedicated on August 25, 1996. When Joe died in 1999, his Plaque was also replaced with a Monument. The original Plaques are now on display at the Yogi Berra Museum & Learning Center in Little Falls, New Jersey. Unfortunately, this is the best picture I can find of them, and the text isn't very legible, due to the glare of a flash bulb.

Baseball

Hall of Fame: Elected in 1974, his first year of eligibility, by the Baseball Writers Association of America.

Other Honors: He was inducted into the Oklahoma Hall of Fame -- in 1964, while he was still playing. When Oklahoma City, the capital of his home State, opened a new ballpark for its Triple-A team, a statue of Mickey was placed outside, and the street was renamed Mickey Mantle Drive.

Teresa Brewer recorded "I Love Mickey" during his Triple Crown season of 1956, with Mickey also appearing on the record. In 1981, Terry Cashman recorded a tribute to all three New York center fielders of the 1950s: Mantle of the Yankees, Mays of the New York Giants and Duke Snider of the Brooklyn Dodgers: "Talkin' Baseball (Willie, Mickey and the Duke)." New York City renamed a school for him in 2002, and the U.S. Postal Service released a stamp of him in 2006.

In 1999, he was named to the Major League Baseball All-Century Team. The same year, The Sporting News named him Number 17 on its list of the 100 Greatest Baseball Players -- a bit low, especially considering that he wasn't even the highest-ranked Oklahoman, with Johnny Bench placed at Number 16.

Depictions: Mickey played himself along with Roger Maris in the films Safe at Home (1962) and That Touch of Mink (1963). Yogi Berra was also in the latter film. Billy Crystal showed an unidentified actor from the back only in his 1992 film Mr. Saturday Night, as a guest on the eponymous character's variety show. In 2000, Crystal made 61*, about the 1961 home run record chase by Mickey and Roger. Mickey was played by Thomas Jane.

Crystal also paid tribute to Mickey in City Slickers, talking about his first live game as a boy, in which Mickey hit a home run. For Ken Burns' Baseball miniseries, Crystal told the story again, and said his first game was one in which Mickey hit the facade in 1956. Mickey was also interviewed for Burns' miniseries.

Although Mickey briefly appeared as a character in the 2007 miniseries The Bronx Is Burning, about the 1977 Yankees, the actor who played him was not identified in the credits.

Quote of Note: "Baseball has been very good to me, and playing 18 years in Yankee Stadium for you folks is the greatest thing that could ever happen to a ballplayer."

Crystal also paid tribute to Mickey in City Slickers, talking about his first live game as a boy, in which Mickey hit a home run. For Ken Burns' Baseball miniseries, Crystal told the story again, and said his first game was one in which Mickey hit the facade in 1956. Mickey was also interviewed for Burns' miniseries.

Although Mickey briefly appeared as a character in the 2007 miniseries The Bronx Is Burning, about the 1977 Yankees, the actor who played him was not identified in the credits.

Quote of Note: "Baseball has been very good to me, and playing 18 years in Yankee Stadium for you folks is the greatest thing that could ever happen to a ballplayer."

this article very good to read.

ReplyDeleteGoogle pixel 2 XL selfie stick

pixel selfie stick google assistant

best selfie stick for google pixel 2

google pixel selfie stick not working

selfie stick compatible with pixel

best bluetooth selfie stick for google pixel